I’m stoked to share the news that the city of Birmingham have given Dame Elizabeth Cadbury her blue plaque this week. She was a Victorian philanthropist who helped to transform education, healthcare and housing at Bournville Junior School (the institution she opened in 1906). The timing feels pretty loaded, arriving months after Belfast unveiled their bronze statues of Mary Ann McCracken and Winifred Carney outside City Hall. Three women. Three different centuries of impact, and one overdue conversation about whose stories get told in permanent materials.

The Other Chocolate Revolution

Dame Elizabeth wasn’t merely playing at the feel-good Victorian charity game. She walked into workhouses as a teen, volunteered at children’s hospitals and in that process saw exactly what poverty did to young bodies and minds. She married into that famous chocolate money and used every penny as ammunition against inequality.

The Woodland Hospital she built wasn’t just for healthcare. It was a statement that slum children deserved the same right to medical attention as wealthy ones. She understood something fundamental that still eludes some policymakers in the twenty twenties… you can’t educate malnourished, exhausted children. You can’t expect excellence from kids who’ve never seen beyond their street.

Cadbury refused to separate social issues; housing, health, education, she saw them all as part of an ecosystem. When World War One brought refugees to Birmingham, she didn’t offer sympathy and prayers. She built homes. At 78, she led the UK’s delegation to the World Congress of the International Council of Women. No retirement on her mind, quite the opposite – even deeper commitment as her influence grew.

Belfast’s Bronze Corrections

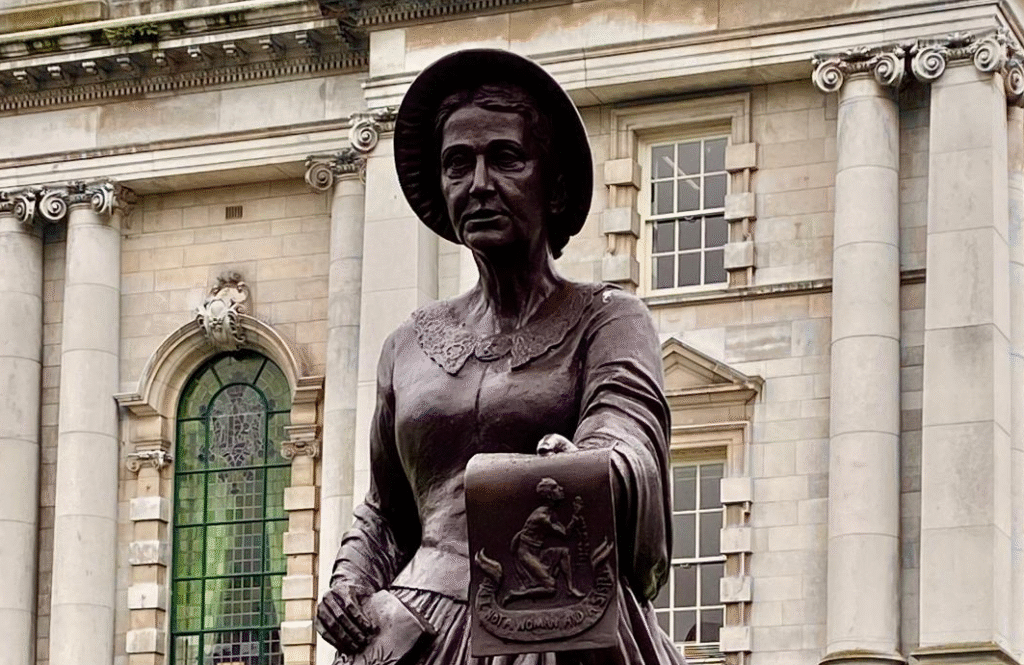

McCracken and Carney getting statues on Belfast City Hall’s lawn feels like historical editing in real time. McCracken was distributing abolitionist pamphlets on the streets of Belfast in the 1800s, wearing her Wedgwood anti-slavery badge like armour. She wasn’t asking for permission to challenge systems built on human trafficking. She handed out evidence, person to person.

Carney’s sculpture captures something different. The only woman inside Dublin’s GPO during the Easter Rising, typing the Proclamation of the Irish Republic while bullets flew past her head. She was James Connolly’s confidante who refused evacuation because the work wasn’t finished. A trade unionist, suffragist, Irish Citizen Army adjutant (that is an officer who assists the commanding officer with administrative tasks), each title representing a unique struggle most of us can’t imagine from our comfy office chairs. Their positions standing right next Queen Victoria’s monument creates an interesting visual dialogue between the different definitions of female power.

Why This Matters to NIWE

When I founded NIWE, people questioned the name pretty much constantly. The New Initiative for Women’s Eudaimonia sounds academic, maybe even pretentious. But eudaimonia is more than just ‘happiness’ or ‘contentment’. The word eludes deeper meanings of flourishing and living aligned with your deepest potential. I feel like these three women embodied that concept before we had corporate frameworks to describe it.

They didn’t wait for permission or structures to exist to facilitate change, they were the architects. Cadbury used chocolate profits to redesign Birmingham’s social framework. McCracken risked her business distributing anti-slavery literature when the economy depended on human bondage. Carney typed revolution into existence while an empire tried to silence her.

Walking past these monuments, future generations absorb their stories as more than historical footnotes. Instead, they have the same permanence as military generals and I love to see it. My two Shepherds, Kiwi and Nana, have more memorials in London parks dedicated to war dogs than to women who transformed education or healthcare!

I think about these women during NIWE’s (and my own) toughest moments. When resources feel stretched, momentum is zero and impact seems invisible. Cadbury organized refugee housing while raising her own six children. McCracken ran a muslin business while fighting slavery. Carney maintained trade union work while reshaping Irish independence. It gives me a healthy dose of perspective

The Uncomfortable Question

Here’s what bothers me about these recognitions. Why did Belfast wait until 2024 to acknowledge these women? Why is Cadbury getting her plaque 107 years after her death? The cynical answer involves International Women’s Day and institutional box-ticking. The real answer, I suspect runs deeper…

Fact is, we’re still uncomfortable with female power that doesn’t apologize. These women didn’t soften approaches, moderate demands or wait for ideal timing. They saw what needed doing and did it, consequences be damned. That’s not the narrative we’re taught about female leadership, even in spaces claiming to celebrate it.

NIWE exists because that discomfort persists. Women in (some) corporate settings still get coached to be less direct, less ambitious, less ‘aggressive’. We’re told to build consensus when sometimes you need to build institutions. We’re advised to work within systems these three women would have already ignored or dismantled.

NIWE isn’t trying to create the next Elizabeth or Mary Ann or Winifred. We’re ensuring the next generation won’t need to wait a century for recognition. They’ll already have claimed it.